As a rangeland conservationist and ranch manager in western Colorado, I have the opportunity to live and work in a land of great beauty. Indeed, the western landscape is what drew me to the rangeland profession in the first place. Over the years, I’ve tried to capture a little bit of that beauty with my digital camera. In the last year or so I’ve been doing a lot of ranch work, and since the ranching world tends to require long hours, I’ve often found myself working in photogenic places during the low-angle amber light of dawn and dusk, and many times I’ve realized that I was standing in a photograph, I just had to pull out my pocket digital, compose the shot, press the shutter button, and a great image was transferred from reality to pixels.

|

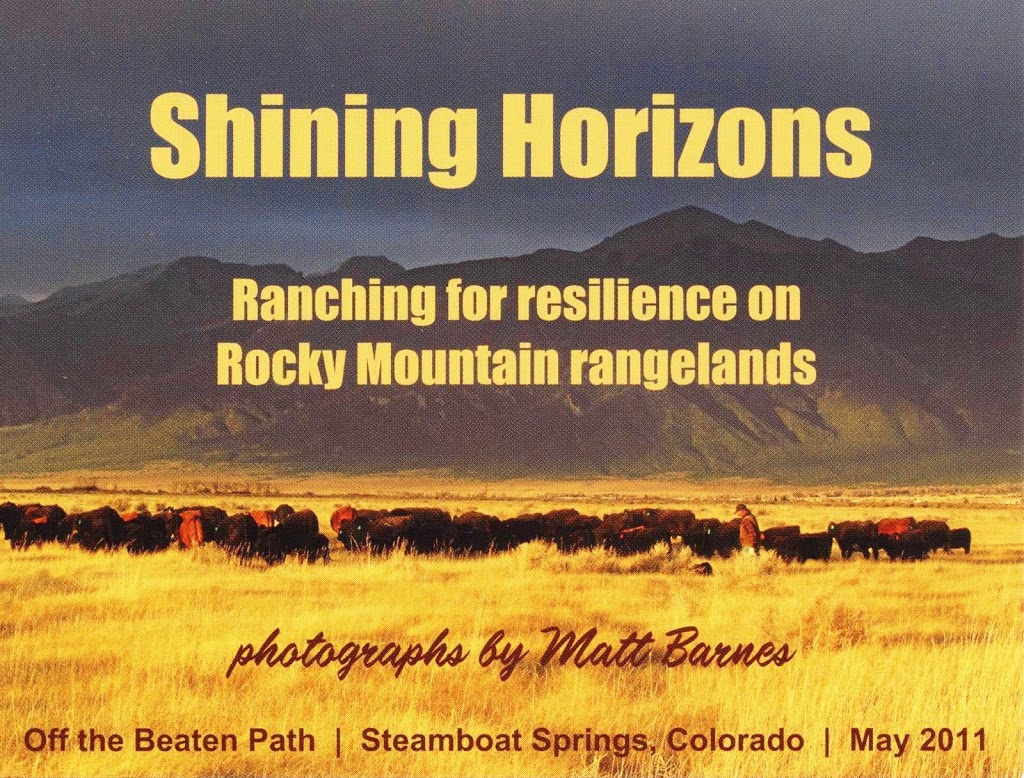

| The Sangre de Cristo Mountains from a ranch in the San Luis Valley |

My photography has progressed from a pursuit of perfect, pristine landscapes to a documentation of living and working on the land. What really excites me, as a land steward, as a writer and artist, and as a citizen, is harmony of humans with the rest of nature—not standing apart, either as directors or as leading actors in front of a static backdrop, but as an integral part of the greater whole: a complex, self-organizing, adaptive system.

The American West is primarily a rangeland landscape, along with forested mountains and, in those few places that can be irrigated, grass meadows or small tracts of farmland. But most of it is still rangeland, because it doesn’t make sense as farmland, ecologically or economically. So, living on the land in most of the West means hunting and gathering, or the natural extensions of those life-ways: herding and gardening. These activities, in and of themselves, are neither beneficial nor detrimental; their impact on the greater whole depends on how they are managed. While in some places we are living with the legacy of poorly managed livestock grazing, there are many examples of livestock grazing where the health of the land is stable or improving.

|

Moving cattle to manage vegetation with rotational stocking on the Baca National Wildlife Refuge.

These cattle will go on to be marketed regionally as organic grassfed beef from Blue Range Ranch. |

These examples of land stewardship for resilience are the heart of the next West, the agrarian West, and a few of them are featured in an exhibit of my best photographs, on display this month at Off the Beaten Path in Steamboat Springs, Colorado.

|

The corral at my summer cow camp,

at the end of the rainbow. |

The exhibit is subtitled “ranching for resilience” because the best stewards recognize that they are part of a greater whole, and they manage for its resilience: the capacity of the system to withstand disturbance and retain or resume its essential structure and function. Resilience goes beyond equilibrium concepts of sustainable yield of any product or even optimization of competing land uses, to embrace a non-equilibrium world. In the long run, nothing can be sustained in perpetuity because the system is always evolving; the ultimate unforeseen consequence of our success is that we create a new reality to which we must then adapt, or be replaced. To surpass sustainability, the goal of land management should be to maintain or enhance the resilience of systems in desirable states, and to find and capitalize on opportunities to improve the functioning of systems in undesirable states.

In so doing, stewards strive to create harmony in landscapes of great beauty. My photographs are an attempt to capture a little bit of this dynamic world of rangeland stewardship.

This exhibit has been an opportunity to share a glimpse of this land of beauty with others, especially those who do not have the opportunity to live it every day. I had a great time talking with folks during First Friday Artwalk — about the West, the land, the life, the art. If you had a chance to stop by and see the exhibit in Steamboat Springs this month, I hope you enjoyed it. If not, you can find many of the photographs on this blog, as well as on my Flickr page.